Jordan Interview

AN INTERVIEW WITH JORDAN

Conducted by Peyton E. Richter[1]

March 30, 1952

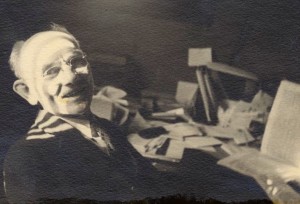

Not many of the great philosophers have been very impressive figures personally. Socrates was snub-nosed and bald, Descartes was frail and swarthy, Immanuel Kant, a broken-down wisp of a man whose silhouette resembles that of a hunched back beggar. One could have taken Elijah Jordan for a typical old mid-western farmer, spending his quiet Sundays at home, contemplating the field he has plowed long ago, the crops he has harvested for countless seasons, the loved ones whom he has seen buried long ago but has never forgotten. The years have not been unkind to Jordan, however. His face is virtually unlined and retains its glow of health. His blue eyes behind his rimless spectacles are unclouded and ever-penetrating; there are still a few dark hairs sprinkled through the white hair which has receded to the back of his head, leaving the round dome of his forehead curving out in monumental proportions. At nearly eighty Jordan is still very much alive physically and mentally. He is not wiry or emaciated in stature, and his voice does not crack when he speaks at length but possesses a volatility and control rare in a man his age. Jordan’s nature seems uniformly serious and contemplative, but with more than a hint of pessimism in his attitude, which one would suspect is a matter of temperament rather than of age.

We sat in his small, unpretentious study which was littered with the books and manuscripts and papers which are the scholar’s stock-in-trade. Jordan sat legs-crossed, facing me across

the room. He tilted his chair back so he could rest his feet on a small homemade stool in front of him, and he would frequently put his thumb under the top of his suspenders when he was particularly comfortable; at other times he would grasp his hands behind his head or stroke his hair. Everything about the man radiated simplicity and calmness. There was not a trace of affectation about him. He talked about the profundities of philosophy with the same degree of practicality that an Indiana farmer would have discussed what amount of fertilizer to use on his crops this year.

We chatted for a while about things in general but finally he brought the conversation around to serious issues and I asked my first question.

*****

QUESTION: Dr. Jordan, it would be interesting to know something of the evolution of your thought, something of the background out of which your individual works have emerged.

JORDAN: I suppose the greatest challenge came from reflecting on the impact of the First World War. One would have to recall the period of prosperity and optimism preceding the war to understand the shock which came with the deluge of suffering – physically, economically, and socially – which was brought about in the first great world conflagration of our century. My own reflective reaction and my own particular problem was: How is one to explain the objective situation which brought home so powerfully the moral bankruptcy of our so-called culture at the very moment when people’s subjective states of mind were running in a completely opposite direction. Almost everyone – except those behind the locked chamber doors – those who really know – expected humanity to soon be reaching the mecca of prosperity which science from the 18th century French Enlightenment on had promised us; instead, came the most fearful rain of blood that the modern world had ever known, the god of progress crumbled – and you as well as I know what the result was. Man had asked for a drink of cool spring water and had received a cup of warm blood. After the war came the lost generation – the Hemingways and all the rest; fatuous optimism soured into self-pitying pessimism (just as it has done after this war, witness the nauseated, nauseating existentialists) and the flight into the illusory epicureanism of the roaring twenties soon followed, only to have the bottom drop out with the depression. This then was the background against which my thinking at the time took place – why did the war happen? What were its real causes? Why should it have come as such a surprise to everyone, to prick the bubble of progress just as it was to reflect myriads of beauty and prosperity? I found my key to the situation and I think it still unlocks the mystery of our manifold difficulties today, when mankind is threatened with permanent annihilation.

QUESTION: And what is that key, Dr. Jordan?

JORDAN: Simply this. What we have needed all along is a corporate politic both in theory and practice. Instead we have had and still have faith only in an individualistic politic. That is what got us into the mess that we are in – the subjective situation – hopes of opportunities for all – was simply the over-side of the objective situation, greedy imperialism and real freedom for none.

Well, it was this realization of the startling difference between the subjective states of mind of men and the objective conditions of men which led me to attempt to formulate a more adequate theory of morals and legislation. I felt, and still feel, that such a theory must have an objective basis or none at all and also that such a theory must revolve upon the notion of corporate person rather than upon the notion of the individual person. For the inspiration of my studies I returned to the unused practical wisdom of the Greeks. Plato and Aristotle were aware of the real problems and very few modern thinkers on political theory have been. The results of my investigations emerged in my examination of the Forms of Individuality (1927) and my Theory of Legislation (1930). Incidentally, the University of Chicago Press is reprinting the latter work this fall and in the new preface I have attempted to say a little of the interrelation of my works.

QUESTION: Would you say that your works form a “system” of philosophy, Dr. Jordan?

JORDAN: No, they do not, at least not in the sense of attempting to present a comprehensive theory of reality which pretends to explain consistently all the facts of human experience. I am very suspicious of system builders in general. Systems easily result in closed rather than open world views and this almost inevitably leads to dogmatism and narrow-minded rationalization. They explain everything – and consequently nothing.

QUESTION: But don’t you think there are certain fundamental presuppositions upon which your thinking has developed, I mean such presuppositions as your notion that the metaphysical whole is more than the sum of its parts or your notion that the realm of fact is analogically identical with the realm of value?

JORDAN: Yes, I think you are quite right, and if by a system you mean a collection of absolute presuppositions which a thinker holds to, I suppose you could say that my writings represent a system. But I would never refer to “my system” as Roy Wood Sellars used to do.

QUESTION: Has your interest been primarily in political theory, Dr. Jordan?

JORDAN: No, I wouldn’t say that. As I have said earlier, my primary interest in the world situation led me to formulate what I consider a more sensible theory of corporate and individual structure. But while I was doing this I became increasingly aware of the necessity of working an objective moral basis for my political thinking. This realization caused me to spend years trying to do just this and you and the others have seen the result of my efforts – The Good Life. Whether I have succeeded in accomplishing my task I don’t know, but perhaps if there is anything worthwhile in my books, eventually it will be recognized. But most of my works, like Hume’s Treatise, have fallen still-born from the press.

QUESTION: Did your ethical studies lead you into your interest and work in aesthetics?

JORDAN: Precisely. But please don’t make the mistake of thinking like so many others that I ever had any intention of presenting in my book on aesthetics any sort 0f theory of art, metaphysical or otherwise. Aesthetics for me means philosophy of value and that is why there is such an integral relation between ethics and aesthetics. I consider ethics to be the science of action and every action takes for granted the worth or value of an object which is the object of action. Furthermore, the only objective basis for preference is to be found in concrete value or aesthetic objects which are the goals of all preferences. One must also remember that the literal meaning of “aesthetic” is feeling and it is only in aesthetic theory that one can discover the real relationship between feeling and cogniti on.

on.

QUESTION: When you speak of feeling, however, don’t you give the concept a meaning rather unusual?

JORDAN: Yes, indeed, for I always speak of the substantiality of feeling. Feeling, for me, is just as real as matter. It is just as much a substance as matter and this is why I go so far as to say that aesthetics, as the philosophy of value, has a place coordinate to that of physics, the philosophy of existence.

QUESTION: Your viewpoint is certainly as interesting as it is radical, but would you make the relationship between aesthetics and ethics a little clearer

JORDAN: I think the easiest way of making this relationship clear is by stating that ethical action always assumes the possibility of the identity of existence and value. You assume when you seek a goal that it is possible to realize your intention in that goal. The object of existence becomes your object of value. Now the relevance of this situation to theory of aesthetics is that it is in art-objects, above all others, that we can perceive the most immediate identity of value and fact which all action aims to achieve.

QUESTION: Could you illustrate your meaning, Dr. Jordan?

JORDAN: Take any art-object, say the Raphael print over my mantelpiece – in this picture of the holy family we see that the artist has used his literal existing materials – canvas, pigments, oils, and so on – to achieve a figurative, meaningful effect. In other words, objects of existence have been transformed into objects of value

QUESTION: In discussing the relationship between value and existence you often speak of the two as being “analogically identical.” This is certainly one point which we frequently puzzle over at Duke.

JORDAN: Not only at Duke is that point puzzled over! But before one can understand analogical identity one must notice carefully the context in which I use the concept. Some people have misunderstood me so far as to consider me a dualist. They get this idea from the fact that I speak of the two realms of existence and value, or nature and culture, and they fail to see that there is no dichotomy here except in thought. The realm of natural objects which makes up the world of nature is identical with the realm of cultural objects which makes up the world of culture but this identity is a peculiar kind of identity – that is why I say that they are analogically identical rather than merely identical. Every fact is a value and every value is a fact.

QUESTION: The is is what bothers me, Dr. Jordan. Is it not in the meaning of the copula that the secret of analogical identity lies?

JORDAN: Yes, for the is, for me, represents the relationship of mutuality and identity all at once. But it is the relation of identity which requires further analysis. If by identity we mean it in the sense of ordinary logic, to say that A is identical with B we mean that A is the same in every detail with B; the two than cannot be different but must be absolutely the same. A coalesces with B. But this notion of identity gets us into all sorts of trouble. Let me give you a. simple illustration from chemistry to make this clear. We say that water is H20. Speaking rather loosely we can say then that water is identical with H20, can’t we? But at the same time in this unity we have a difference, two parts of hydrogen and one part of oxygen are united to form water but, nevertheless, each element retains its unique differences from all others. The problem of identity and difference, of unity and variety, is a thorny one, to say the least, as Plato pointed out long ago. But my point is that a different notion of identity is required to explain the simplest instances of this real relation. This is why I use the term analogical identity. A fact is identical with a value not in the sense of being the same but in the sense of standing in identical analogical relations with a value. Analogy, then, has its meaning in its being the mode of inter-reference of existence and value as they constitute reality.

QUESTION: Your remarks on analogical identity certainly throw new light on the notion but I fear it remains beyond my comprehension yet.

JORDAN: Don’t feel badly about it. Sometimes I fear that it escapes my comprehension too! But if you recall what I said in The Aesthetic Object about the categories of the logic of existence and the categories of the logic of value perhaps we can discuss analogical identity more fruitfully from that point of’ view.

QUESTION: I do recall that in The Aesthetic Object you take a rather Kantian approach to the problem, in fact you seem to argue analogously to Kant all through the work in discussing existence and value. You say that just as space is our a priori form of intuition of outer sense by which we know objects of existence, so is color our a priori form of value cognition of outer sense through which we know value objects. And corresponding to time as our inner sense of existence cognition is tone as our inner sense of value cognition. But when you say that time and space are analogically identical with color and tone which in turn are analogically identical with each other, I must confess I get rather lost. Could you enlighten me?

JORDAN: By saying that space and time are analogically identical I mean that they are correlates or interdepe

dent. In this respect I am only saying what Alexander said earlier and I agree with him that space-time is the primordium of existence. But, as I see it, one must also have a primordium of value, too, and this primordium is analogous to the substance of existence, it is the substance of sensation or feeling which is to be understood in its valent or value aspects as color and tone.

QUESTION: This does seem to make sense, Dr. Jordan. If I recall correctly you showed the relation of analogy between color and space by saying that one always experiences color as spatial and space as colored. In the same way one can understand the analogical relation of tone and time by saying that one always experiences tone as timed and time as toned. So color and tone, as correlates of space and time, can be considered identical with space and time but the identity must be conceived in a unique sense?

JORDAN: Yes, and this unique sense of identity is precisely what I mean by analogy. The identity is not actual but real; it is not literal but figurative.

QUESTION: Dr. Jordan, is one correct in associating your philosophical views with the objective idealist view-point? In ethics, for example, some thinkers see in your ethical theory a direct development of objective theory from Bradley through Royce to you. I noticed in the Chicago University library card catalogue that E. D. Bucker wrote a thesis in 1950 which he entitled “Bradley and Jordan, two approaches to an objective ethic.” What do you think of the validity of viewing your philosophical views as being representative of objective idealism or even Hegelian?

JORDAN: Many have labeled my views Hegelianism but they are mistaken if they think that I have been greatly influenced by Hegel or that I have imitated his ideas. I have never read any considerable amount in Hegel and if some of my views match Hegel’s it is for other reasons. However, if I tell you of my intellectual background, you will see how nearly right those who view me as an objective idealist are.

QUESTION: It will be interesting to hear this. Could I persuade you to start at the very beginning?

JORDAN: If I begin there I will have to start with the cosmogony of all things and neither of us would ever live to see the completion of the tale. No, I shall not use Dewey’s genetic method upon myself. But if I were giving you my life history I would begin a hundred years ago when my father, fresh from England, came up the Mississippi River and settled in lower Indiana. I grew up on a farm, taught school for ten years, and even before I went to the University at Bloomington, I had developed philosophical interests but mostly from a reading of the English poets from Milton to Keats. But when I went to Indiana University I met Warner Fite and it was his lectures that gave me my first philosophical impetus. Under his direction I read seriously a philosophy book for the first time.

settled in lower Indiana. I grew up on a farm, taught school for ten years, and even before I went to the University at Bloomington, I had developed philosophical interests but mostly from a reading of the English poets from Milton to Keats. But when I went to Indiana University I met Warner Fite and it was his lectures that gave me my first philosophical impetus. Under his direction I read seriously a philosophy book for the first time.

QUESTION: What was that first book, Dr. Jordan?

JORDAN: It was Royce’s World and the Individual. If you are looking for other idealistic influences upon my development, I will tell you that I was at Cornell when idealism flowered under Creighton.

QUESTION: Did you find much of interest in Bradley’s works?

JORDAN: Yes, a good deal. But while Bradley expresses many interesting and important insights, he never really escaped the subjectivism which has shot through the development of modern philosophy since Descartes.

QUESTION: It appears that your chief philosophical goal has been to escape this subjectivism in metaphysics, epistemology, ethics and aesthetics. Am I correct in supposing that in each of these areas that you propose to arrive at objectivity by means of your principle of corporate individual?

JORDAN: Yes, this is my basic concept which I first worked out in my investigation of the forms of individuality. It seems obvious that an individual is always known through the relations in which he stands to other individuals and to cultural institutions, which are objective structures in which individuals live and move and have their being. For example, John Smith’s individuality is constituted by his institutional connections.

QUESTION: How do you go beyond Bradley’s viewpoint. He certainly says the identical thing in his essay “My Station and Its Duties”.

JORDAN: But Bradley never was able to get from the individual to the world; he had no clear notion of the corporate nature of individuality; he never obtained objectivity in his metaphysics or in his ethics, and for the same reason. The principle of the moral person is corporeity and persons are persons only because they embody the principle of corporeity. Thus I speak of corporate personality, of a super-individual will who is empowered by its body of cultural objects and who has a will of its own through which it effects changes in the constitution of society and causes events to occur in the world structure.

QUESTION: But, Dr. Jordan, when you go so far as to say that the only person that can really act is the corporate person it is exceedingly difficult to understand exactly what you mean.

JORDAN: Yes, it is difficult. Difficult to analyze, because of the complexities involved in the multi-dimensionality of the total corporate structure and still more difficult to understand because of the limitations of our finite theoretical equipment. That is why the philosophers who have attempted to come to grips with the obscurities of natural and cultural experience are very often accused of obscurantism. When I say that it is always the corporate person who acts I mean simply that when we think that we are acting, in reality we are acting always in and through some aspect of the corporate nature. In that sense we act in the corporate person or, better, the corporate person acts through us. Certainly we see corporate persons acting every day – as churches, as states, as schools, as industries, and so on. I do not see that an “individual” can act outside of a corporate structure for the very definition of his individuality depends upon his corporate nature, upon the inter-connecting institutional relations which make his individuality possible. I read somewhere in a paper recently that an Episcopal church in Washington had bought a dumping lot in order to transform it into a playground for children. No single individual was responsible for this action. It was the corporate person or the church who acted.

QUESTION: One question I’ve been wanting to ask you which may be nonsensical: Do you conceive of the various corporate persons as composing a sort of ultimate corporate person, an all-embracing one who represents the totality of reality?

JORDAN: I suppose you are afraid to formulate this question more precisely? Do I believe in the Absolute? Isn’t that what you really wanted to ask me?

QUESTION: Of course. But I hesitated to use the term. You certainly avoided the term in your Good Life though there are places in the book where one almost had to substitute the concept of a metaphysical Absolute in order to make sense out of a passage. There is a passage in The Aesthetic Object, however, where you actually come out and define the Absolute as being the total unity of Space-Time-Color-Tone.

JORDAN: By that I meant that the system of nature and culture may be considered as a kind of ultimate cosmic whole. But I do not see that such a conception of an Absolute is empty or meaningless in the way that Schelling, for example, conceived it – as a sort of aesthetic fog of metaphysical stardust. The Absolute is not the super-real; it is the Real, that is to say, it is the natural-cultural affective-cognitive continuum.

QUESTION: I have an idea that you have said a great deal more in a few words than my feeble brain can ever comprehend. If one could expand your definition of the Absolute apparently one could get a Jordanian-Einsteinian view of the cosmos, only one would have to speak not only of a space-time factual continuum of existence but also of a color-tone valent continuum of culture.

JORDAN: But don’t forget that the two continuums are in reality one; that is to say, they are analogically identical.

QUESTION: Here we go again. The concept of analogical identity seems to be as central in your philosophy as the Idea of the Good was in Plato’s.

JORDAN: You may have said more than you mean. For Plato conceived the Idea of the Good to be the principle of order and intelligibility and in a sense one could say the same of my principle of analogy. Were the realms of existence and value not analogically identical there would not be the intelligibility of which reality is constituted.

QUESTION: You mean the real would not be rational and the rational would not be real?

JORDAN: I prefer not to put it in such an Hegelian manner but I suppose one could put it that way. But as I put it in The Aesthetic Object, existence-substance is space-time just as value-substance is color-tone. Together these are the constituents of reality in that they are identified through their common factor of intelligibility. It is intelligibility which is the ground principle of the cosmos; without this principle nothing but chaos would exist.

*****

Here the conversation did not end. In the course of what followed Jordan expressed his views on such varied topics as mysticism, logical positivism, the history of American philosophy, the skepticism inherent in religion and science, and even entered into fascinating discussions of plant physiology and the light-theory of Newton and Goethe. He spoke with a lucidity alien to his writings and he illustrated his points with simple, homespun analogies. One could imagine what a stimulating and provocative teacher the old man once must have been. But he said that he had just about lost interest in teaching when he was ready to retire, for by that time the students who were coming into his classes had already become so infected by the false values of our “machine-ridden, money-mad, epicurean so-called civilization” that he couldn’t do much for them.

Elijah Jordan now feels that his life, like his work, is almost finished. His last book, Business Be Damned, has been carefully proof-read and is in the hands of his publishers. His doctor has given him warning that his life-time battle against subjectivism must soon come to an end. Have all his efforts been in vain? Will his books be as neglected and misunderstood in the next half of this century as they have been in the first half? E. Jordan is not in the least concerned. “If there is anything good in my books,” he said just before I left him, “it will eventually come out. Perhaps you will be around to see. I don’t have to worry. Time will tell.”

[1] Peyton Richter received his PhD in Philosophy from Duke University. His dissertation, supervised by Prof. Glenn Negley, a student of Jordan, was entitled, “The Metaphysical Foundations of Jordan’s Aesthetics.”